Scattered across colonies on the islands of the southern Adriatic, Scopoli’s shearwater (Calonectris diomedea), Yelkouan shearwaters (Puffinus yelkouan), and Audouin’s gulls (Larus audouinii) lead secretive lives. In the southern Adriatic, Audouin’s gulls reach the northern limit of their distribution range and are present in small groups that often change colony locations between breeding seasons. In contrast, Scopoli’s shearwater and Yelkouan shearwaters visit their colonies mainly at night, when their nests, hidden in rocky crevices and underground burrows, resound with loud, scream-like calls. For this very reason, the sight of one of these species in flight is truly unforgettable.

However, the islands on which they establish their colonies are not home only to lizards and Mediterranean scrub. In rock crevices, among the branches of dry vegetation, and within the nests of Scopoli’s shearwater, Yelkouan shearwaters, and Audouin’s gulls, a quiet and little-known predator lurks—while several camera traps continuously record what even dozens of field researchers cannot: the tense struggle for survival between invasive predators and seabirds.

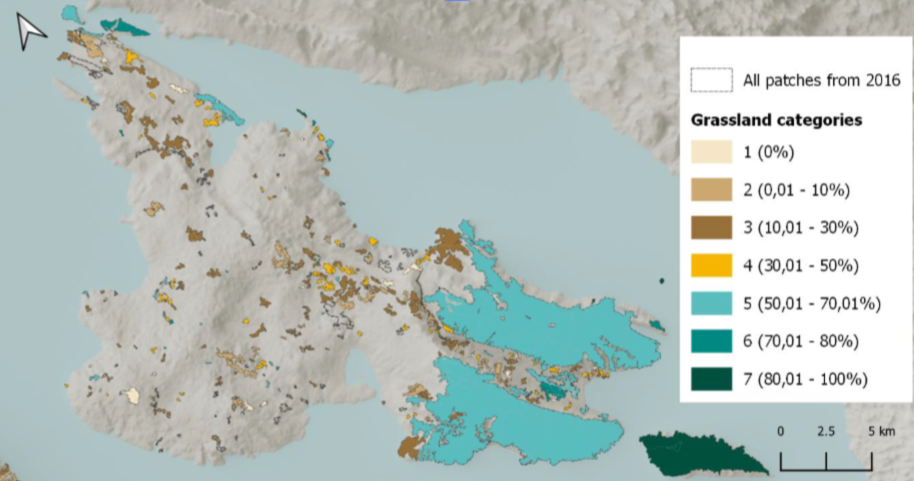

Among the many threats facing seabirds today, predation on eggs and chicks in the nest stands out as one of the most significant. Like many other long-lived species, these birds reach sexual maturity only after several years, lay a small number of eggs, and breed just once per year. Therefore, the loss of eggs and chicks represents not only wasted reproductive effort but also a serious threat to population size and stability. While nest predation has always been part of the long evolutionary history of birds, numerous non-native mammal species brought significant threat to survival of island species. Because of the negative impacts these species have on local bird populations, they are classified as invasive. One of the most harmful species affecting seabirds globally is the black rat (Rattus rattus). Preventing and mitigating the damage caused by rats to seabirds on Croatia’s offshore islands was the main objective of the recently completed LIFE Artina project and continues through further research and conservation efforts within the LIFE TETIDE project.

Camera traps, or motion-activated field cameras, represent one of the most effective tools for studying seabirds. Their continuous operation in diverse field conditions and their ability to store large volumes of images bring the complex interactions of breeding seabirds closer to scientists in ways that were unimaginable until recently. Camera-trap data have been widely used in research on the behaviour and ecology of many species and are particularly valuable for studying elusive species such as Cory’s and Yelkouan shearwaters. Despite their usefulness, processing the large volumes of data collected can be a major challenge. During the LIFE Artina project, over 300,000 photographs and videos of these species were collected, which would require several hundred hours to review manually. For this reason, we turned to artificial intelligence as a new method of data processing in order to build upon existing knowledge of seabirds.

Although the use of artificial intelligence to analyse photographs and videos has been present in the field of nature conservation for more than half a decade, many existing programs have been trained primarily to detect larger species, such as ungulates. Systems designed to detect birds and nest predators, however, remain extremely underexplored. Using a subset of LIFE Artina data (approximately 70,000 photographs and videos from the nests of Audouin’s gulls, Scopoli’s shearwater, and Yelkouan shearwaters), we decided to test MegaDetector, one of the most widely used artificial-intelligence models for wildlife detection.

Over several months of work, MegaDetector processed all of the prepared photographs, while BIOM’s ESC volunteers Lena and Anastasis diligently reviewed the same dataset, allowing us to compare the results and assess MegaDetector’s accuracy. Our research to date shows that MegaDetector demonstrates the same level of reliability when detecting birds as it does with other types of datasets.

The study itself was presented at the 6th Croatian Symposium on Invasive Species, which provided an opportunity to initiate discussion in an international setting on the study and control of invasive species, as well as to connect with many colleagues interested in our work. Although the path toward a better understanding of the complex interactions between birds and nest predators is a long one, the first results are promising, pointing toward faster and more efficient research that could help ensure a safer future for seabirds.

Written by Matija Vodopija