Luka Škunca from our Habitat and Botany Programme writes about his first visit to Sweden and the sixth workshop on monitoring Natura 2000 species and habitats. During his stay in Umeå, he participated in lectures, field visits, and exchanges of experience with colleagues from all over Europe.

Written by: Luka Škunca

At the end of September this year, I visited the Swedish city of Umeå,a place I had never visited before. It is the largest settlement in the region, located six hours by train north of Stockholm. This peaceful town in a subarctic landscape hosted a workshop on integrating new technologies into species and habitat monitoring, organised by the Eurosite association and the Horizon project Biodiversity Meets Data, with the Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences as the host.

This was the sixth workshop focused on monitoring Natura 2000 species and habitats, with the first one held back in 2013 in Wales. The workshop is designed so that participants present their projects and methods through lectures, defining the issues they are monitoring, designing monitoring programmes, decision-making in management, and planning restoration activities for target species and habitats. Over four days of a packed schedule, numerous presentations were delivered by scientists, experts, and protected area managers from across Europe, from Sweden to Spain. The third day concluded with a field trip to a habitat restoration site for the White-headed Woodpecker (Leuconotopicus albolarvatus). The lectures were grouped by theme, starting with marine and coastal habitats, followed by ecosystem services, habitats and vegetation, neural networks and applications, integration of field and remote-sensing data, species monitoring, and monitoring management and restoration outcomes.

Among the presentations that impressed me, I would highlight the one by the Swedish Environmental Protection Agency, where we learned about the full scope of monitoring activities they conduct, as well as the long-term budget dedicated specifically to monitoring. Monitoring of Natura 2000 species and habitats is carried out at the national level using remote-sensing methods (primarily Sentinel-2 satellite data) and intensive field research based on unbiased, balanced sampling across ten landscape units. In addition, monitoring is also carried out at the county level, along with targeted surveys for individual threatened species and habitats. They also regularly conduct thematic mapping of the entire country, such as land-cover maps, forest productivity mapping, or soil moisture assessments.

As expected, most presenters presented methodologies involving satellite and/or drone data in their research and status assessments, and many examples demonstrated how these technologies are applied, as well as software that enables simple data processing. One particularly interesting example comes from Sweden, where satellite data are used for regular environmental mapping across the entire country—as well as for specialised projects such as mapping lichen cover. Since lichens are an important food source for reindeer, their distribution affects reindeer populations and can be a source of conflict with the Indigenous Sámi community. Throughout the workshop, it was clear that drones have become standard field equipment in much of Europe. For instance, in Belgium they are used for mapping heathlands in collaboration with the public (using both official and visitor-submitted drone data), in the Czech Republic they track the spread of invasive plants in mountain grasslands, and in Spain and Sweden they are used to map and monitor hard-to-access habitats such as floodplains and cliffs.

As expected, most presenters presented methodologies involving satellite and/or drone data in their research and status assessments, and many examples demonstrated how these technologies are applied, as well as software that enables simple data processing. One particularly interesting example comes from Sweden, where satellite data are used for regular environmental mapping across the entire country—as well as for specialised projects such as mapping lichen cover. Since lichens are an important food source for reindeer, their distribution affects reindeer populations and can be a source of conflict with the Indigenous Sámi community. Throughout the workshop, it was clear that drones have become standard field equipment in much of Europe. For instance, in Belgium they are used for mapping heathlands in collaboration with the public (using both official and visitor-submitted drone data), in the Czech Republic they track the spread of invasive plants in mountain grasslands, and in Spain and Sweden they are used to map and monitor hard-to-access habitats such as floodplains and cliffs.

I was particularly interested in presentations on monitoring habitat restoration, with examples from Wales and the Czech Republic offering several ideas applicable to the restoration of wet grasslands planned within the project Restoring Wetlands: A Pathway to Biodiversity and Ecosystem Resilience, which we are implementing together with Vransko Lake Nature Park. In Wales, they first developed a set of criteria for prioritising habitats for restoration, which helped them identify coastal habitats as the top priority. They then defined favourable conservation status using quantitative criteria, allowing them to assess through monitoring whether the target condition was being achieved (and if not, adjust management accordingly). A similar approach was used for mountain meadows in the Krkonoše Mountains, where a favourable status and a transect-based methodology were defined to determine which meadows were improving and which were not (the transect starting point is always the most favourable part of the meadow, enabling spatial assessment of good and poor areas). Another interesting presentation introduced the EAGLE concept—a land classification model designed to harmonise habitat and land-cover classifications through a three-element structure: land cover (e.g., grassland), land use (e.g., pasture), and characteristic properties (e.g., dry pasture undergoing shrub encroachment).

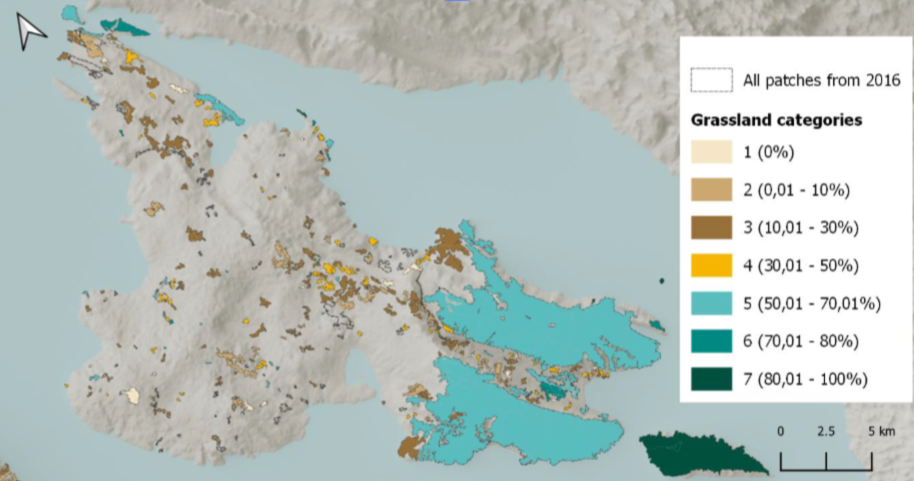

In addition to the main programme, an engaging part of the workshop was the session where participants could briefly present their work or describe challenges for which they sought advice. I used this opportunity to present the challenges related to mapping wet grasslands—one of the prerequisites for restoration in the area of Vransko Lake and Ravni kotari. After my presentation, I received several excellent suggestions on how to approach mapping habitats best distinguished by the duration of flooding during winter and spring (in summer, these grasslands dry out like the rest of Ravni kotari).

The afternoon of the final day was reserved for a field trip to a habitat restoration area for the White-headed Woodpecker, one of Sweden’s most endangered bird species, threatened mainly by the lack of suitable habitat within large areas of deciduous forest. The restoration project began in 2017 through cooperation between the County, Municipality, and Forest Agency, supported by volunteer actions to inform the public and set up feeding stations.

Today, ten partners are involved, and restoration work has taken place at fourteen sites. These activities include thinning forest stands, removing conifers, and leaving sufficient dead wood to provide natural food sources. We visited one of the restored sites. Although the area may not look particularly impressive in photographs, the story behind it—about the dedication and persistent effort of all partners to conserve this endangered species—left a lasting impression.

Alongside the rich lecture programme, the workshop also offered a memorable personal experience—my first visit to Sweden and to a subpolar region, as well as my first encounter with the northern lights. Although the moment sounds magical, the reality was rather modest: seen from the city, through a veil of light pollution, the aurora appeared as a pale, translucent cloud drifting quietly across the sky. Only in photographs does its true colourful beauty reveal itself